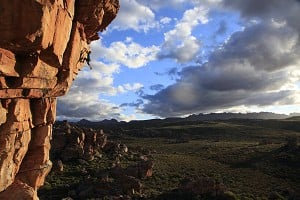

Robbie Phillips gives us some tips and tricks on how to make sure our climbing doesn't disturb the birds that we share the rock with, as well as some cautionary tales from his own climbing career.

Every crag we climb at is home to birds - regardless of whether you're bolt clipping on the limestone, dangling off a wild Scottish sea cliff, or between burns on your mossy gritstone boulder project.

But birds in the UK are in real crisis, with their population facing massive declines to the tune of 73 million birds lost over the last 50 years.* As climbers we enter into their habitats, we climb on their homes, so it's only right we should act responsibly and do everything in our power to prevent disturbing or causing them harm.

I have been a passionate climber for eighteen years and a naturalist my whole life. Climbing for me is not only a way to experience the thrill and exhilaration of movement on rock, but also a means to connect with nature.

So as we approach spring, I have written a guide to climbing etiquette when dealing with birdlife.

We'll look at:

- The nesting season (When + How long?)

- How to avoid disturbing birds

- Practical advice for the approach

- What to do if you stumble upon a nest on a climb

- What the Law states

It's also important to understand that the protection of birds is taken very seriously in the UK, and we have many laws surrounding the disturbance of birds that we as climbers must abide by.

The Law - What it states and what you need to know

Preventing disturbance of birds and their nests is more than being a responsible climber, it's also keeping on the right side of the law. Disturbance to birds is described as any human activity that causes them to exhibit behaviour outside of their norm, so regardless of whether you are aware of any bird bans, if you're caught disturbing nests there could be legal ramifications.

What you need to know is:

All British bird species are protected - The Wildlife and Coutryside Act 1981 stipulates that it is illegal to kill, injure, or take any wild bird, take or damage the nest of any wild bird whilst in use or being built. The eggs of all wild birds are also protected.

In Scotland, there is extra protection provided by the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. Here, the Act states that (in Scotland only) it is illegal to 'intentionally or recklessly…take, damage, destroy or otherwise interfere with the nest of any wild bird while that nest is in use or being built…or obstruct or prevent any wild bird from using its nest.'

So in Scotland, disturbing any bird near its nest could be illegal, if it is deemed that you are "interfering" with it or preventing the bird from accessing its nest. In England and Wales, it is only illegal to take or damage the nest/eggs and disturbance is not included (though there exists a grey area of whether keeping the bird away from its nest for a significant period would effectively count as damage if it caused the nest to fail).

Some are exempt outside of nesting season – Birds listed in Schedule 2 of the Wildlife and Coutryside Act 1981 can be killed if the intention is to kill them. As climbers, I don't think this part matters too much, as we are not going hunting.

Schedule 1 birds have additional protection (Only those with a licence can go near an S1 birds nest) – This list changes depending on where you are in the UK, but includes birds such as the Golden Eagle, Osprey, Peregrine, Barn Owl, Snowy Owl (Full list is here)

The significant difference in Schedule 1 legislation (for England, Wales and Scotland) is that it is illegal to 'intentionally or recklessly disturb any wild bird included in Schedule 1 while it is building a nest or is in, on or near a nest containing eggs or young or disturb dependent young of such a bird.' These birds get specific protection against disturbance—just being near the nest could be an offence.

Remember: the law isn't just there for show, many climbers have been caught, whether oblivious to the disturbance they had caused or not, and there can be serious consequences!

Since then the law was changed to be more specific on the type of disturbance and introduced a definition of disturbance response (See here).

The lesson here is to always keep up to date with bird bans and restrictions, especially when visiting crags or areas you haven't been to before.

When is the nesting season?

If you know when the nesting season is, you'll have a better idea of what to look out for on an approach, and what to expect if you come across a nest. The more information we have, the better prepared we can be!

The UK bird nesting season starts in early-February and continues to as late as September, however there are some birds like the wood pigeon which nest all year round. There are four different stages of the nesting season and these can vary from year to year depending on many factors such as weather, availability of food, disease, etc…

Below is a rough guide so you know what to expect:

Stage 1 is finding and building a nest. During this period the risk is relatively low as there are no eggs, but caution still needs to be taken as you wouldn't want to damage or disturb a possible nest site.

Stage 2 is laying and incubating the egg. This is a high risk stage as the eggs need to be kept warm and protected from predatory animals. If a nest is disturbed and the parent bird flies away, this can cause the egg to cool which may damage the embryo, or even leave the egg vulnerable to predatory animals.

Stage 3 is when the egg hatches and is replaced by a chick. It does vary between species, but often when a chick has hatched, the parent bird will be less likely to abandon a nest as a considerable amount of effort has gone into hatching the egg. Saying that, disturbance should be avoided at all costs as chicks have fewer defence mechanisms than adults and could easily become prey to predatory animals.

Stage 4 is when the hatchling is ready to fly away. At this stage the fledgling chick is usually pretty strong and capable of looking after itself although it could still appear chick-like in appearance.

Nesting season is different for all bird species and the stages can fluctuate depending on the season, so use these approximations alongside common sense to make good judgments whilst at the crags – if it doesn't feel right, then it probably isn't.

A recent study in the Journal of Animal Ecology found that many birds are laying eggs up to a month earlier than they did 100 years ago (most likely due to symptoms of Climate Change). So be aware that while rough dates in books, on websites and on signage are a good guide to follow, they may vary from year to year.

How to avoid disturbing birds nests

What is Disturbance?

Disturbance to birds is described as any human activity that causes them to exhibit behaviour outside of their norm. Any departure from their typical behaviour, especially when they flee from the disturbance, requires them to expend additional energy, which can often have negative consequences.

Examples of abnormal bird behaviour could be:

- Abandoning a nest or chick

- Aggressive behaviour to humans

- Stress behaviour e.g. feather plucking or self injurious behaviour

Here is a step by step guide to things you should do to prevent disturbing any bird-life when going climbing:

Check if there are any RESTRICTIONS or CLOSURES

Before you even leave for the crag, you can check if there are any existing restrictions or closures at the place(s) you want to climb at.

Scotland (Mountaineering Scotland)

https://www.mountaineering.scot/access/birds-and-nesting

England + Wales (The BMC)

https://www.thebmc.co.uk/modules/RAD/

Ireland:

Contact should be made with local climbers, or with https://www.mountaineering.ie/ Alternatively, contact the local National Parks & Wildlife Service office for sites in the Republic of Ireland (see https://www.npws.ie/contact-us) and Northern Ireland Environment Agency for sites in the North.

If you are out climbing and see or suspect nesting birds, get in touch with whoever above suits your region. They all rely heavily on communication from local climbers, walkers and those working in outdoor spaces to keep information up to date.

If in doubt, do not climb the route, it's not worth disturbing a nest and risking prosecution. Find somewhere else to climb—it's not your right to disturb birds just for your own fun.

Look before you leap!

Keep to trails where there is one – this will prevent destruction of habitat and maintain wild spaces for all creatures big or small to enjoy. Also, some birds are Ground-nesting, and if you take a shortcut through a moor or woodland, it is possible you may disturb or possibly destroy nests and eggs without even knowing it!

Stay alert and be observant of your environment - From a distance you may observe birds hovering above the crag and this could alert you to a potential nest site. If birds appear distressed at your sudden appearance then that's an obvious sign you're near a nest site. Some, but not all birds will dive bomb you if you get too near - I have been dive bombed by Bonxies, Gulls, and even Owls on one occasion.

Keep noise to a minimum – Sound is the first thing likely to cause disturbance to birds from human activity. Using common sense here is key: if you suspect there are birds nesting close by, cracking out the portable speakers to blast out some Drum and Bass is probably a no-no.

Dog owners must keep a tight leash – I love my dog and she loves to play and bound about in the heather. I keep her close unless I already know the area is clear. Unless you're confident there is no risk to disturbing nesting birds, keep your dog on a leash. Dog walkers are one of the groups that have caused the biggest declines in ground nesting birds (such as Terns on beaches in England). Even if your dog is friendly, the bird doesn't know that and it will cause them lots of stress, meaning they use lots of their energy.

TOP TIP: a small pair of binoculars can be a good way to observe birdlife from a distance, also helping to identify the species so you can provide accurate information later to climbing associations or local nature groups.

We all make mistakes from time to time and looking for shortcuts is often how I've made mine. I thought I'd share a prime example from my own climbing where a simple shortcut almost led to disaster!

My heart sank as I realised what I'd almost done, and we tiptoed carefully back to the trail we'd come from and took the long way round.

What to do if you stumble onto a nest whilst climbing?

In my 17 years climbing I have come across birds' nests many times whilst climbing and on approaches! If you haven't yet, it is only a matter of time.

Below I have outlined a set of actions to take whilst on the wall if you should come across a nest (listed in order of priority):

Keep your cool! - If you are halfway up the wall and come across a nest, the first thing to do is make sure you are safe; the last thing you want to do is hurt yourself.

Descend - The best option would be to descend straight away, but if this is impossible for whatever reason, then the next best option is to try and avoid it.

Can you avoid? – Maybe there is a traverse onto another line you can take, but occasionally there isn't, so in this situation maybe you have to climb past it.

Climb past - Do so quickly and quietly. If Trad climbing, try and tell your climbing partner so they don't come across the nest unawares.

To prevent other climbers possibly causing a disturbance, please reach out to the climbing governing body that represents your area and/or local wildlife organisations to update them on nest sites.

IF THE ROUTE IS ON UKC YOU CAN LEAVE A NOTE IN THE 'FEEDBACK' SECTION, WHICH WILL MEAN ANYONE THINKING ABOUT CLIMBING THAT ROUTE WILL KNOW THAT THEY SHOULD LOOK ELSEWHERE WHILST THE BIRDS ARE NESTING.

In recent years it has come to my dawning realisation that no matter how much we try to avoid nests on routes we climb, if they exist, we will be disturbing them in some way.

She was very relaxed with my presence with a wonderfully bemused look on her face, and thankfully no vomit to share. I brought my climbing partner Emma up to join me, and we did our best to give the mother Fulmar a wide berth before Emma set off on her pitch. However, shortly before I started to second, the fulmar flew off, disturbed by my sudden movement!

I felt a great pang of guilt seeing the lone egg (fulmars only lay one in a year and won't lay again until next year) but decided that the mother would probably return soon enough… but then just as I started climbing, a gull swooped in and took a shot at the egg! It missed, but this event suddenly sent me into guardian mode as I stayed put until the fulmar returned.

The gull came back again, but I shooed it away, before the fulmar mother finally returned to her egg. If that gull had taken the egg, it would have been my fault, and the guilt would have been a heavy burden on me. From that moment I realised that no matter how hard we try, if nests exist on a climb, there is not a lot we can do to avoid disturbing them! You will always be putting the birds in danger with your presence, so the best action to take is to back off. After this incident, we backed off the route and left Hoy. The following year I returned to Hoy to climb 'The Longhope' again, this time a month earlier to avoid the eggs.

What else can you do to support the protection of birdlife at British crags?

Everything I've outlined above is what you need to be a great steward and protect the birdlife living on our crags, but what else can you do? Educating our climbing and outdoor community is probably the greatest power we have, so share this knowledge wide and far:

- Talk to your climbing partners about it.

- Share this article on your group community pages/WhatsApp groups, on social media, and anywhere you feel it would be relevant.

- If you're an instructor or guide, I think educating beginner outdoor climbers is one of the most powerful things we can do.

I have always felt that as climbers we are intimately connected to our environment, and it is our responsibility to care and protect it. Taking these steps to care for our local British birdlife is just another way we can become brilliant stewards of our crags and environment.

*British Trust for Ornithology Survey 2023

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Cochamó: Multipitch Madness in Chilean Patagonia 3 Aug, 2018

- SKILLS: The Process: Training with Robbie Phillips - Ep. 5 24 May, 2016

- SKILLS: The Process: Training with Robbie Phillips - Ep. 4 24 Mar, 2016

- SKILLS: The Process: Training with Robbie Phillips - Ep. 3 11 Jan, 2016

- SKILLS: The Process: Training with Robbie Phillips - Ep. 1 & 2 27 Nov, 2015

- Training to Become a Better Climber - Part 5 12 Apr, 2012

- Training to Become a Better Climber - Part 4 13 Dec, 2011

- Training to Become a Better Climber - Part 3 21 Jul, 2011

- Training to Become a Better Climber - Part 2 9 Jun, 2011

- Training to Become a Better Climber - Part 1 5 May, 2011

Comments

Great piece Robbie!

Really good article Robbie, nice one!

It surprises me that the Barra isles remain unrestricted. With prime climbing season coinciding with prime nesting season I can't see this lasting much longer. Climbing here is not going to get any less popular. The right/wrong person will eventually kick up enough stink about it.

What is the best course of action, get it while you still can, or avoid for obvious reasons?

I ran this article past an RSPB coastal habitats expert with plenty experience of human interference, she reckoned it was spot on. Re Pabbay/Mingulay, it is a bit strange, but NTS will have consulted with the BTO on this and will presumably take action if there is a problem - so the best course of action is to follow Robbies advice.

I've only climbed on Pabbay (in late June) but I was surprised how little overlap there was between prime climbing terrain and nesting ledges. Looking back at my photos (we took kayaks so had a good look from the sea too) there's almost no guano at all on the main crags. I don't think that's because the birds have been scared off, there simply aren't enough suitable ledges; very different to Hoy or Cilan for example. So I don't think there's much rationale for a seasonal climbing ban here, although climbers exploring new areas should always be cautious. Given current population trends the bonxie colony on the east end is perhaps the only concern but there's no climbing in that area.

There probably is a conversation to be had about the number of climbers camping and toileting though. The NTS warden was on the island at the same time, so they have an eye on things, numbers felt ok but if they doubled, say, I think you might need a rethink.

Mingulay is obviously much bigger and complex. As I say, I haven't climbed on there but I have been on a birdwatching boat trip right round the island, through the stacks, arch etc. My impression was the main seabird areas & are not climbed on, mostly because the ledgey terrain (e.g. Biulacraig) that is good for nests is not so good for climbing, while the stacks etc are pretty inaccessible even to climbers. So while there's perhaps some scope for formalising the separation of these zones, with the tiny numbers of people doing exploratory new routes and the way the Scottish access code works, the current approach as outlined by Robbie's excellent article would seem sufficient at least for now.