Culm Dancing - A Second Wave (1968-73)

Back in the day, when climbing was an anti-sport and climbers were eccentrics, romantics, rebels or drop-outs, every Sunday the dear old Exeter Climbing Club boarded the bus and journeyed down to Chudleigh Rocks. Occasionally there were 'meets' when a Bedford van would be hired to trundle through Devon lanes to more exotic venues like Haytor or The Dewerstone, and even once a year to far-off Bosigran in Cornwall. It was known that climbing had been done in other places, but the prevailing wisdom was that they were loose and chossy and not worth trading for a precious Sunday on the perfect limestone of Chudleigh.

By 1967, changes were afoot. The 'Royal Navy Mountaineering Club' (no less) had published a guidebook not only to the whole of Devon but also a chunk of Cornwall, and a more exploratory faction began to emerge in the Exeter club. At first everyone's energies were focussed on the sea cliffs of Torbay, which had seen forays since the early 60's but which really took off after John Hammond and Steve Dawson climbed Gates of Eden at Daddyhole. However the new guidebook pointed the way to other parts of Devon, principally the north coast, and before long the 'explorers' were taking a look.

In those days if you didn't have a car Devon seemed vast, and using a combination of buses and walking to reach the crags left a lot less time and energy for climbing. I was still at school, years from owning a car, but lucky enough to team up occasionally with people like John Fowler, whose succession of fast cars not only seemed to shrink the county but gave an exciting edge to the climbing day. Inspired by the guidebook, in July '68 we blasted northwards in John's Lotus-Cortina to check out Wrecker's Slab. For some reason we didn't climb Wreckers that day but did manage to put up the first route at Gull Rock - a single pitch climb called Argonaut - discovering to our surprise that Culm could be acceptably solid. This proved to be an isolated trip.

Over the winter of '68/9 Torbay again saw all the new route action, and by April Frank Cannings and I were putting up routes like Dreadnought and The Hood at Berry Head. Simultaneously on the north coast, Bristol-area climbers Ian Duckworth and Bill Chevrest made a major discovery - the mighty shale precipice of Blackchurch. They proceeded to battle their way up the most obvious crack line to create Loose Woman (HVS + A2), perhaps the first really steep route to be climbed on shale. They were also the first climbers to sleep in the old summerhouse at the top of the crag, saying what a great doss it was but with one drawback….it was haunted...

Earlier in 1969 John Hammond and I had taken a trip to Baggy Point, an epic journey involving first a walk to Exeter bus station, then a bus ride to Barnstaple, then a local bus to Croyde, and then 3 miles walking to the crag - at least 3 hours in total. It was a miserable day but OK for exploration – we descended by Scrattling Crack then traversed southwards, noting many impressive lines including a fine pure corner. We then shifted to the top of The Promontory and began cleaning two striking lines side by side – John on the future 'Urizen' and me on 'Lost Horizons'. After our labours John announced that the climbing on his line would be very boring – the same move over and over – and that if he ever returned to climb it he would call it 'One Track Crack'. As it turned out he wouldn't get the chance.

Both Steve Jones and I had driving licences by 1969, and on rare occasions we were granted the use of our family cars. On April 20th Steve's folks obliged and we drove to Baggy Point, not only getting there in under an hour but driving right to the top of the crag, as you could in those days. We made for the right-angled corner I had spotted with John and put up Resurrection (HVS), so called because it was the first substantial route to be recorded at Baggy since 1898! Also I believed it could spark off a renaissance in Baggy Point climbing. The renaissance happened, but not in the way I expected. In October '69 Tony Willmott and a team from the North London Mountaineering Club descended on Baggy and kicked off by climbing the blatant line of Urizen, which John Hammond had obligingly cleaned. Willmott was pretty soon joined by other strong leaders like Ben Wintringham and Al Baker and over the next 18 months Baggy Point was developed 'under the radar' by the NLMC. Eventually crag pictures appeared in Mountain magazine criss-crossed with route lines, to the astonishment of certain local stars who felt that their patch had been invaded!

The early months of 1970 were very cold, even in Devon. Ian Duckworth had been urging me to get to Blackchurch and an opportunity presented itself in February when Pete Biven took a car-full of us to the north coast. It was damp and chilly and we only climbed one route – Rite of Spring on Blackchurch Rock – but I was really fired up by the main cliff and particularly by the awesome groove line of Archtempter. I was at college in Bristol at the time and climbing mainly with Frank Cannings at the weekends, either in the Wye Valley or Cheddar Gorge. Routes like Big Brother at Wintour's Leap and Brainbiter at Cheddar date from this time. Frank had introduced me to a mate of his from Bangor University, Graham Skerratt, who moved to Bristol at the same time as me. Whilst at Bangor Graham achieved notoriety for a fall he had taken at Tremadog, when a box of matches in his jeans pocket had ignited and he set fire to himself. Graham and I formed a strong partnership on the FA of The Bilk at Avon, when he had held my first proper lead fall in spectacular style with a waist belay on a single 9mm rope. He was definitely a belayer you could trust, and as an added bonus he had transport - a little green mini-van. He had never climbed in Devon so when the Easter break came I persuaded him to sample the delights.

I had a few objectives in mind. On the way down we stopped at Baggy and climbed a big chimney in Scrattling Zawn, naming it Egg (as it was Easter….Graham's idea). Then after a night at my folks place in Exeter we set off again for Blackchurch, arriving in time to do some cleaning of the mega groove line. We also sussed out the summerhouse for a doss and it looked perfect – clean, dry and in a secluded spot in the woods above the crag. At that time it was in sound condition, having a wooden floor and wooden ceiling with a trapdoor into a loft space. Haunted? It didn't look it. Graham was keen on his beer so we drove to a decent pub that night, getting back towards midnight and trudging up through the woods to the summerhouse with sleeping bags and mats.

It was pitch black and around 2am when the noises began, first just loud enough to wake us up then becoming much louder. It sounded like something large and heavy was dragging itself along the floor of the loft. I felt my heart-rate triple, reached for a torch but couldn't find it so just withdrew into my sleeping bag and waited for what would happen next. Suddenly the noises stopped and there was dead silence again, broken by Graham saying hoarsely "What the f**k was that?" Neither of us felt like investigating, or moving at all, and even when it was light next morning we weren't inclined to explore the loft.

The ascent of Archtempter took a full day. There was a freezing north-easterly and a few flurries of snow. Much of the time our hands were numb and we got dozens of cuts from shards of shale as we cleaned vital holds. I only had one nut large enough for the corner crack on the second pitch so it felt bold, but the satisfaction of topping out on that amazing line was something special, among the top new routes I'd done up to that point. That evening we weren't tempted to stay in the summerhouse again so we headed further down the coast and slept in the van, the next day climbing at Brownspear Point, where after repeating the excellent Main Sail (hardest culm route in the RNMC guidebook) we climbed a steep HVS corner. Unfortunately Brownspear proved one of the less stable culm cliffs and both routes collapsed a few years later.

For a time the most avid explorer in the Exeter CC (and one of its great eccentrics) was John Hammond. He was a gentle, cultured man who, rather than going into a thriving family business after university, chose to 'drop out' and live in a squat in Exeter. He never claimed state benefits but lived by working every now and then and eating very cheaply. He once told me he could live well on £1 a week (about £16 in today's money – still feasible!). For a while he used to carry around a large earthenware pot of cooked lentils and just dip in to it every time he felt hungry. I'd had some great times climbing with John in Torbay and the Dolomites, but I was away at college when he began exploring the culm crags. He was enthused by one in particular – Lower Sharpnose Point. There were a couple of Diffs mentioned in the guidebook and in December 1970 John climbed a new VS with someone I barely knew at that time – Keith Darbyshire. Keith already had something of a track record having done a crumbling new route on Cornakey Cliff a couple of months earlier, but living out of town he was on the fringes of the Exeter group. At Sharpnose John also got half way up another impressive line - the future 'Clawtrack'. Anyway, he told me I should take a look at the place so I enlisted a strong climbing partner who just happened to have transport - Martin Chambers. Martin had been with me on the FA of Crow at Cheddar 3 months earlier. I hadn't climbed much since then as I'd quit my college course and focussed on making money, working long shifts at an engineering factory in Exeter.

One weekend in early February 1971, Martin and I drove up to Lower Sharpnose in his Morris Countryman (a car partly constructed with wood, now a classic!). These days, above Lower Sharpnose there is a massive 'Listening Station' covered with high tech equipment and security fences. Back then there were only two radio telescopes and you could drive right to the clifftop. There was also an abandoned farm which gave a great doss right above the crag. On the Saturday we traversed in from the north side of the point and explored a bit before a fast-approaching tide got us thinking about climbing out. We opted for a roof-capped corner on the end of what is now called the North Fin, and climbed up to a big ledge at 10m to escape the tide. I climbed the corner crack on the second pitch but got stopped by a large detached block at the overhang. After messing around there for far too long I decided I couldn't pass it safely and retreated to the ledge, which by this time had big waves surging past it into the bays either side of the fin. We were stranded, with only a couple hours of daylight left. It was clear that one of us was going to have to swim. I lost the toss and was lowered on a single rope into the water where I half-swam, half-surfed into the bay, taking the rope with me. Luckily in those days there was an easy ridge between the North and Middle fins, and even soaked and shivering I was able to climb out and drop Martin a prussick rope. Next day we abseiled in, trundled the block and climbed the line - Hatchet, HVS. Not a major route compared to others at Sharpnose but a memorable visit which made me very keen to get back there.

A chance came on the first weekend in April with Steve Jones, no doubt one of us persuading their parents to lend a car. We put up The Smile (E1) that day, which followed a rising break across the shady North Fin to a lovely sun-kissed wall to finish. About the same time I teamed up with Keith Darbyshire on a new route for the first time. We completed the line that John Hammond had tried and dubbed 'Clawtrack'. We initially gave it a different name but 'clawtrack' perfectly described the wavy crack line on the second pitch and John was keen to see it used.

Keith and I hit it off big time – we were both totally fired-up by the climbing potential of the north coast and both at the stage of pushing the limits in all aspects of life, not just climbing. By April 17th Keith and I had done the first routes at Pentire, Tintagel, Backways Cove and Doyden Point, and although this article is a paean to culm, from that moment onwards our plans and dreams were mainly focussed on what became known to climbers as The Atlantic Coast.

However the Culm still had some great days in store for us. Before April was out, another trip to Sharpnose saw Keith leading the first ascent of the superb Lunakhod and me leading a perfect 'lightning bolt' jamming crack on a fin between North and Middle fins. This has since fallen down…a common fate on this coast. By May I was sick of working indoors and quit my job to take part in a legendary 'expedition' to Lundy on a Naval landing craft. After this I moved down to Cornwall, joining Ian and Sandie Duckworth to work on a farm at Porthcurno. With long days of hard manual work and soloing on the crags most evenings, I felt the strongest and fittest I had ever been in my life. Unfortunately most of the people I knew who were free to climb were still in Devon! The record shows I got back there for one day at least on June 11th, when Steve Jones, Ben Goodman and I attacked the left side of Blackchurch Cliff – the highest part of the crag and then untouched. It was their first visit to Blackchurch. Steve led up to a pinnacle then I led off diagonally rightwards, making for an obvious hanging slab which would complete the climb. The ground was loose but not technical and I got to a decent-sized ledge. When Steve joined me on it all was well, then Ben arrived and the weight of all three of us sent the ledge crashing off into the void, leaving us hanging from the belays. At the top of the route I told them I already had a name for it - The Almighty (as a counterpoint to Archtempter). "The almighty pile of sh*t?", Ben quipped. I had some faith that we had put up a notable climb however, and as the easiest route on the crag it got quite a few ascents and cleaned up nicely, even making it into Bill Birkett's 'Classic Rock Climbs in Great Britain', before the inevitable happened.…a rockfall on pitch one made it two grades harder and its popularity dwindled.

By 1972 Keith and I were on fire as a team and ready to try anything. Il Duce was climbed in April, an ascent which took us right to our limits in every sense. A couple of days later I climbed Darkinbad with Ian Duckworth, then while visiting Steve Jones in Truro hospital (he had taken a nasty lob at Bosigran) I checked out Carn Gowla with a college friend and that sparked another series of ascents. The good old culm wasn't getting much of a look-in that year, however Keith did hone his loose rock skills on a couple of new routes at Cornakey, and I had a useful day at Lower Sharpnose with Hugh Clarke when we climbed Mascon and a mean line called Uphill. It would still be a few years until serious training became established in climbing and sustained climbs on the big faces at Lower Sharpnose became possible – the crag was yet to give of its best.

On the weekend of April 6th and 7th, 1973, Keith and his dad Brian Darbyshire hosted an Alpine Club meet on their farm in Devon. Pete Biven and John Cleare took charge on the Saturday and a large contingent of fit and less fit people were taken along Magical Mystery Tour at Berry Head. It was a hilarious epic which none of us who took part will ever forget. People plummeted into the sea from various heights, were dragged out and had to continue to climb soaked to the skin - there is no upward escape. One of the local Devon team, Hugh Clarke, actually gave himself a hernia pulling one of the more portly AC members out of the sea. On the Sunday it was Keith's turn to choose the venue, and he chose Lower Sharpnose Point. Most people were pretty wiped out from the day before and seemed to be hanging around a bit, so Keith and I split off to climb an attractive groove line on the South Fin (Dulcima, HVS). Biven and Cleare were keen to climb something new with the group and started messing about at the seaward end of Middle Fin, which was then unclimbed. Eventually conventional tactics failed and they devised an 'Alpine' rope manoeuvre, somehow throwing a line over the fin and securing it so that people could prussick up to where the ridge was easier-angled. Keith and I had the bizarre view of a long string of people going alpine-style up the ridge of Middle Fin. The weird and wonderful Alpine Groyne (VS + aid) is probably now the only unrepeated route at Sharpnose.

By 1973 Keith was my firm climbing partner in the SW. I was away at college in term time and climbed with a different crowd, but for big SW adventures Keith was the man. He was game for anything - the wilder the better. On reasonably solid rock I could lead a good grade harder than Keith but on loose rock he could take me well out of my comfort zone, as I discovered when trying to repeat The Parson (XS) which he'd led in 1971. In climbing and in other aspects of life, when most people would start to apply the brakes, Keith would step on the gas. Driving with him could be nerve-shattering, especially as the passenger seat in his minivan wasn't bolted to the floor. We'd both done a 'stage two tune' on our cars, putting in over-sized valves which increased engine revs considerably. I could get nearly 100mph from my Morris Minor and Keith about the same in his mini. We had some insane races. Once when I'd been ahead for a while in narrow lanes suddenly a semi-airborne minivan slewed onto the road in front of me - Keith had driven across a grass bank to pass me on a corner. Another time I was behind Keith but there was no sign of him on a long straight where I'd be bound to see him. I backtracked and spotted the tail end of his car, completely buried in a hedge. The game was to get everywhere as quickly as possible, the more so when it was somewhere you were dying to get to, like a crag in North Cornwall. Gripping tales about Keith were legion, and still are amongst a small band, and in some ways that is the easy way to remember him. It is more painful to think of the man himself, the big, grinning, bouncy, untamed character that he was, and what he might have achieved had he not lost his life in 1975.

Most of the time Keith and I climbed 'ground-up' but from 1973 when we didn't think a line would go free in that style (or not result in a decent route) we operated a system of 'cross gardening', where each of us would clean a line for the other to lead on-sight. It worked really well at Gowla but less well at Blackchurch, where I couldn't face cleaning some of the lines Keith wanted to climb. So it was me that ended up cleaning Savage God while Keith laboured at the other end of the crag with his farmer's trenching tool, toiling away at some horrendous fault destined to become The Sexton or Barrabas. Fifty years ago the left end of Blackchurch wasn't as green as it is now, and Savage God was a lovely clean-cut groove of grey, slightly crystalline rock. Nowadays a green sheen persists on that end of the cliff, perhaps due to a warmer, wetter climate that has affected many north-facing crags throughout Britain.

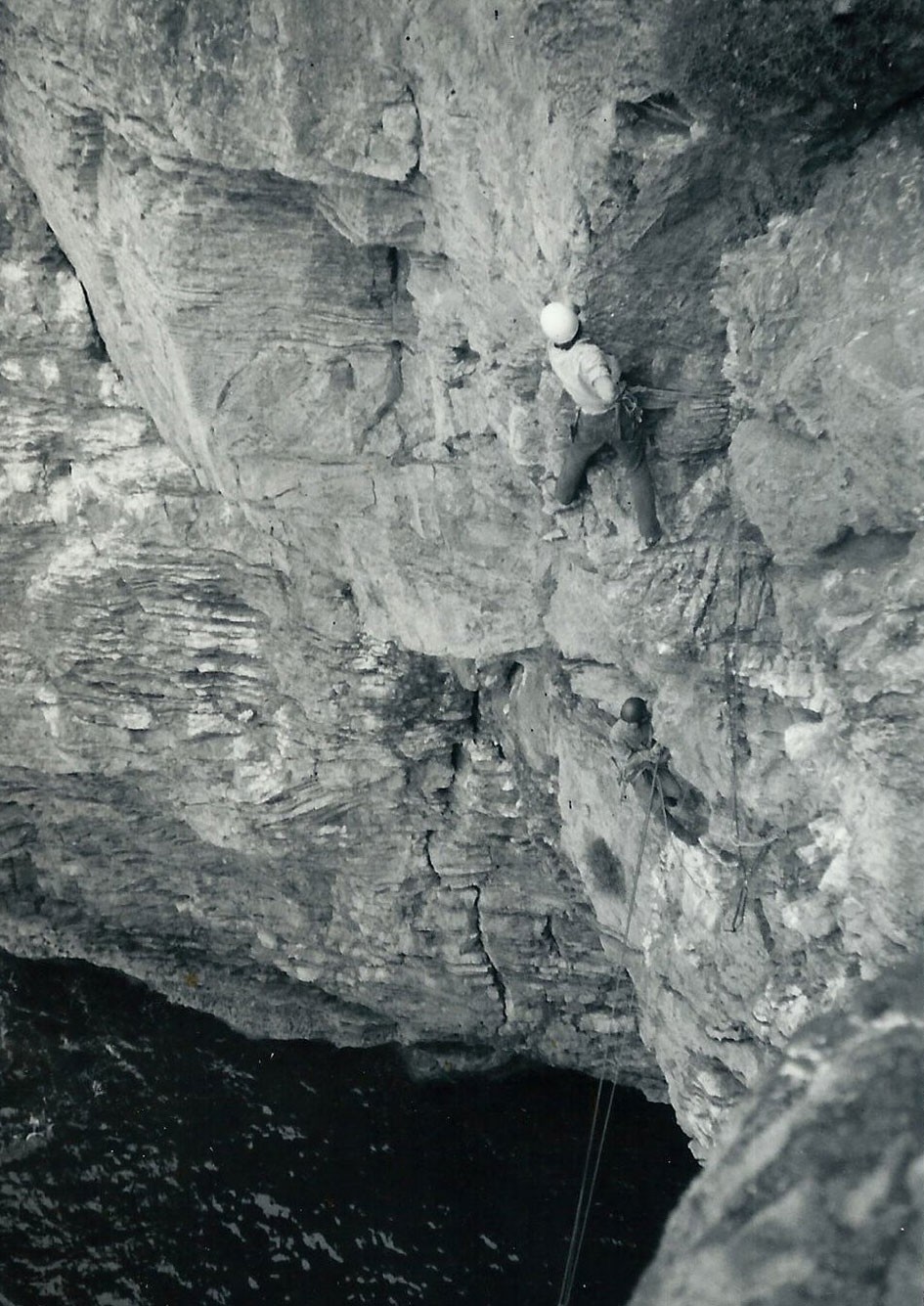

It was September before we could attempt Savage God. My best pal at college, Nick Rourke, a non-climber who was very handy with a camera, joined us for the day and took an iconic picture that has appeared in many guidebooks and magazines. By that time I had done most of the routes at South Stack and I thought Savage God stood comparison with them. In our minds it confirmed Blackchurch as the top culm crag, an accolade which expired a few years later when the faces of Lower Sharpnose became laced with fantastic wall climbs.

By 1974 the culm climbing scene was changing. I still came home to the SW for college holidays but usually had to find paid work, just snatching the odd day out with the boys. Keith was the driving force by then and became drawn to the bigger, looser shale cliffs, such the Eigerwand of culm – Henna Cliff. Surprisingly he had a supply of willing (or gullible) seconds, foremost of which was a young journalist from 'up north' - Dave Garner.

Dave takes the story from here...

Postscript. In 1968 the now rebranded 'Royal Navy and Royal Marines Mountaineering Club' published an updated 'Devon Rock Climbs' guidebook. Once again Bob Moulton edited it, and wrote all the Dartmoor material. Al Baker wrote Baggy Point and I was asked to write the rest of the north coast. My area straddled Devon and Cornwall so the problem was what to call it. The 1966 guidebook had called it 'The Hartland Point Area' but this seemed wrong when some of the crags were 20 miles from Hartland Point. In a lightbulb moment I hit on 'The Culm Coast', which seems to have stuck and felt just right, like a good route name.

For more information visit The Climbers' Club website.