Niall Grimes writes about his early days of climbing in Donegal...

When I was little, I hardly knew what the world was, nor my place in it. On the dinner table there was a salt and pepper set, two little cubes of glass with silver tops, and they both sat inside a round plastic holder with the world printed on the outside. On the top was a gold-painted eagle and you used the eagle to lift the top half off and get at the salt and pepper. I would sit at the dinner table and use the eagle to spin the globe and look at the different shapes painted on: Africa, Greenland, Black Sea, Sicily, Antarctica. I liked the names but they really meant nothing to me because all I knew was Violet Street and Chapel Road, the Convent Field and the Triangle.

I went on a few holidays in my early teens to odd parts of Ireland, saw monasteries, shopping centres and beaches, but I didn't really get to know any of the world until a few years later. In my late teens, I became involved in the sport of rock climbing.

My best friend's brother was a climber. Paul's brother, Raymond, had started climbing a year before and he would tell us about his magical experiences. He used words we had never heard – Epic, Pumped, Psyched – and while I didn't really understand, I was enthralled. In the Scout hut I found a climbing magazine and flicked through the pictures and learned the names of the equipment. Paul and I pleaded with Raymond to take us out and one day he said he would.

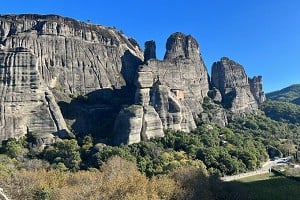

A winter's day, in a deep and dark November. Simon and Garfunkel rattled from the stereo of Raymond's Golf as we left Derry and wound down the old road to Letterkenny. Beyond here we took ever smaller turns into wetter and greyer lands, hills and bogs. The car stopped at a place that didn't look like any place at all and we were here. I got out. I had never been to these places before, as we didn't have a family car, so even by getting this far I was feeling like a Polar explorer. Raymond pointed to a piece of scenery:

"That's the Poisoned Glen."

In the distance was a range of scoured hills, steep-sided and gloomy. They were half-dressed in snow, the white tops disappearing into visibly-moving clouds. In the centre was a gouge, about a mile wide and a mile deep, and round the sides of this cauldron, as the boggy ground grew steeper, were streaks of grey rock, tilted and featured with corners, cracks and slabs. To each different buttress of rock, Raymond gave a name: The Castle, Ballanageeha Buttress, Main Face.

We laced up boots and heaved on rucksacks and followed him into the mountains. The times when I had begged Raymond to take me climbing, I had entertained visions of monkey swinging and dangling on a rope like some natural adventure park. Now, as I traipsed in silence through foot-sucking bogland, I was becoming aware of a different reality. I had long since left anything I knew as a comfort zone. Ahead, I saw the mountainsides and gathered that we were destined for the steep smears of rock that grew ever more overhanging as I approached. The fact that I was going to have to confront these things became clearer to me. The mountainsides radiated a primordial threat, and my nostrils flared with a haunted sense that I got while watching horror films. But I can't do this thing, I thought to myself.

By the time I caught up with the others at the base of the rock, it reared above me. The rock was riven with salivating fissures, looming overhangs and gloomy niches. All around black hills watched, uncaring. The air was cold and my clothes were damp. I tied-in to the rope and Raymond led off up an overhanging crack. He cursed the whole way up, and laughed. The effort and fear were so present, so obvious, that they were comical. At the top he sat on a ledge and, safeguarded by his rope from above, I battled up the ferocious crack.

I was terrified. Terrified that my feet would slip, that my hands would give out, that my arms would uncurl, that the rope would break. That I would need to try even harder, that I wouldn't make the next move, that I would make the next move, that I might have to give up and that I might yet become even more terrified. At the top I laughed, the way you might laugh at a car crash.

We sat on a tiny, sloping heather ledge. I felt the rope and the climbing equipment tug me towards the safety of the rock face and sensed its security. This tiny security felt like everything, as all around me the world seemed wild and dangerous. The mountains, the weather, the climbing, the emotions. All these were new to me, and the simple tug of the rope was all I had to focus on for hope, like a Hail Mary at an exorcism, or a Geiger-counter in a nuclear apocalypse.

It wasn't an easy day out. It wasn't a comfortable day out. It certainly wasn't a fun day out, but as we drove home that day, aged sixteen, I felt I had just had the most amazing day of my life so far.

Surprisingly, as I had little aptitude for it, I kept climbing. Intermittently for the next couple of years, then more and more, with a small circle of old friends and new ones met through climbing. I bought my own equipment and a guidebook to climbs in Donegal. This listed different ways up each cliff, which crack each one took, which delicate line up each slab, and gave each its level of difficulty. It also gave the name each one had, and who had been first to do it and when.

Tarquin's Groove, Hard Severe, T. Kenny and F. Winder, 1955.

The names and descriptions had an air of magic. I would wonder who those people were and how things had been in their times. We would do their climbs and make up things about them. Over time we got better at climbing, did the Severes, the Very Severes, the Hard Very Severes and the Extremely Severes. After that we started to do new climbs of our own, looking for possibilities that matched or extended our abilities.

Ruthless People (E4 6b), E4, N. Grimes, A. Millar, 1990

Elvis (E3 6a), E3, N. Grimes, D. Millar, 1991

Flesh (E5 6a), E5, N. Grimes, B. Callen, 1992

For years I went to Donegal at any opportunity and explored cliffs for new lines. We would drive to the loneliest parts of the county, scanning roadsides and hillsides for undiscovered bits of rock. We wandered along seaside paths hoping the coastline would steepen up enough to give us a challenge, and often our wish was fulfilled.

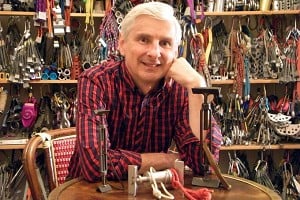

In the end, my desire to climb more took me away from Ireland, but Donegal had become a home of sorts. I got to know it very well and love it greatly. The three years I spent climbing there and developing the crags were some of my best times. I have new climbs that bear my name in many quiet corners of the county, each the result of much effort, the outcome of inspiration. In the end I wrote a guidebook to Donegal, detailing all the new development my friends and I had been involved with.

Years ago, I would go to the Waterside Library and open out maps of Donegal and examine them. I would follow roads and try to find the places I had gone. The changing colours showed different heights and I would recognise hills. Contour lines ringed these hills and they would huddle together at the steepenings that we would seek out for our cliffs. Then I would look at other things: rivers and little spots that had names. I would know these places. Sometimes there would be a couple of ruined houses in these places. Other times there would be nothing. Absolutely nothing. Just a piece of bare boggy ground. Yet someone had once been here and named it, perhaps even lived there somehow, and it had meant enough for them to give it a name. Now, bare land.

I think often about the climbs we did, how much we put into them and how much they meant to us. These obscure routes in obscure places were everything to us. We dreamed of them all week and did all we could to have the freedom to get there and the skills to succeed when we did. But times pass. I have left there, and I don't know if people climb there anymore. Heather will grow and cover over the precious rock. Climbs will disappear back into the land.

I imagine someone finding the guidebook, with its obsessed detail and its directions, its names and numbers, and going and finding the places where we climbed. And seeing nothing.

- ARTICLE: The Edge of Time 14 Feb

- GEAR NEWS: Boulder Britain 2020: Bigger, Better, BOULDER! 20 Oct, 2020

- PODCAST: Jam Crack Podcast 6 Dec, 2016

- The Pitter-Potter of Giant Feet: 'Meeting' Dean Potter 20 May, 2015

- REVIEW: Roca Verde Climbing Guide 28 Jul, 2014

- Coming Home for Christmas 24 Dec, 2011

- A New Guidebook: Boulder Britain 22 Nov, 2011

- King Of The Crag 10 Sep, 2011

- Psychovertical by Andy Kirkpatrick 15 Jan, 2009

- Jerry Moffatt?s Revelations - Master's Wall 12 Jan, 2009

Comments

Brilliant. Don´t think I´ve ever read a better piece about starting climbing; every sentence resonated. Thanks Niall!

Beautifully written. Thanks.

Cheers Niall - a delightful read on my birthday. Oh, to be young again!

This is great Grimer. I was wondering just this week if you had written anything recently.

Si.

Lovely read! So emotive, when you bringing out your book? 😎👍