George Ponsonby recalls post-lockdown adventures in Chamonix...

19th March 2020. Matt and I were packing up to leave Chamonix to head back to Ireland. The hope that this virus thing would only last for a couple of weeks was rapidly dissipating into the ether, kicked out the door by the helicopters the PGHM started sending out above the Chamonix to spot climbers. That and the wartime-esque speech Emmanuel Macron delivered managed to penetrate the bizarre bubble of unreality that surrounds the Chamonix valley and let us know this would probably be a long haul event.

So with no notion of when paycheques would return, or how long it would take the French bureaucracy to sort out the paperwork to pay the now unemployed masses, we did what all good young independent adults did and ran back to our families in Ireland to weather it out. We knew we'd be straight back as soon as we could.

Lockdown over and heading straight back to Chamonix, with the usual apprehensive mix of feelings about whether it's worth heading there or not. The further the start date from an Alpine trip I am, the more psyched I am to head out. As the departure date approaches, the more I find myself looking for excuses to stay – climbing in Ireland is amazing and there's nowhere I have been that's more enjoyable than spending days at Fairhead, Owey Island or Ailladie, scaring myself on amazing routes without the fear of the whole crag collapsing on you or a big mountain storm moving in.

There wasn't much Matt or I could do in preparation for the climbing either – in my case being stuck in Tipperary until the week before we left due to the lockdown with my dad, my granny, the dogs, the farm animals and a lonely robin that would fly into the kitchen to eat scraps (apparently they like companions, and we were the only ones). The only mountain nearby was more of a gently inclined bog in my opinion. In true Irish style, when I could finally test myself on some of the more adventurous routes around Ireland, the weather obviously crapped out and I spent a week in Ailladie and Muckross climbing in between and during storms. I must have been the only person who wished for bad weather during the lockdown – it feels like there is only so much good weather Ireland will give you in a year, and it decided to give it all when we were all stuck in place.

The 7th of July rolled around, Matt turned up in his van and we were off. Driving to Holyhead, the ferry over to France and most of the journey through France went fine, however towards the end, the first of several funny incidents/mistakes occurred that seemed to characterise a lot of what we did bar the actual climbing. Driving along the French motorway at 3 a.m., both of us delirious from fatigue, I was making the third batch of coffee in the passenger seat in the JetBoil when I let my concentration wander and it boiled all over my lap, resulting in some pretty painful burns. The largest one would alternate between a scab and an open wound whenever the scab was torn off by climbing over the next three weeks, adding more bloody patches to all my climbing trousers.

Over the next couple of days, we faffed about, tried to catch up on sleep, went sport climbing and did a quick lap on the Cosmiques ridge for 'acclimatisation.' There was a 3-day weather window starting the third day after we arrived, and from previous experience with Chamonix summers, I knew it could possibly be the only one. There were three big 'grand courses' that Matt and I really wanted to try, and we settled on an attempt of the American Direct on the Drus for this weather window. It had been climbed the previous week, the weather wasn't very warm - which would hopefully minimise the chance of rockfall that the Drus are famous for - and being at the lowest altitude of the three choices, we thought it would be the best bet for our unacclimatised selves.

We were so unprepared – sleep deprived, unacclimatised, no proper climbing for months – and we so didn't care. The lockdown had supercharged our psyche and I was willing to push it way further than I had on previous trips. People say that the mountains will always be there next year,' but with global warming, there's a chance the perennially collapsing Dru may actually not be. Therefore, at midday of day 3, we hopped on the Montenvers train then began the long, long slog up to the bivvy at the base of the Petit Dru.

We were 'fast and light' novices, and our bags let us know it. However, with two days of food, sleeping bags and pads, crampons, axes and the rock rack there wasn't much we could shave off. Our bags became heavier when Matt found what he was sure was a massive valuable gem, and in the sack that went. We also found some abandoned gear, roll mats, slings and carabiners and took whatever we thought would be useful.

We had a 4 a.m. start the next morning, separating our gear into 'leader' and 'second' sacs. We were off. Matt started off in the lead and we simul-climbed the first 8 or 9 pitches to the base of the first substantial pitch, the 40m 6b corner. I was finally able to ditch the heavy second's bag and shouldered the comparatively featherweight leader's bag which still had crampons, a sleeping bag and pad and two days of food in it!

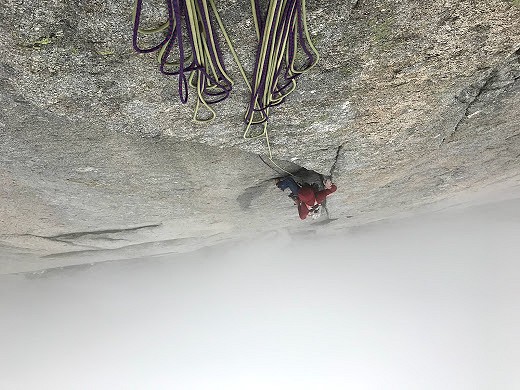

Setting off up the corner, I quickly realised that we didn't bring any gear big enough for the crack and ended up having to quickly climb from one ratty-looking fixed piece of gear (usually an old wooden peg) to the next, not wanting to French free the pitch in case the gear was all too shite to pull on. I climbed as quickly as I could to get it over with and given that there was not too much gear, I was able to flow through the jams and laybacks. We continued on through the cloud line that was hanging halfway up the mountain, to the massive house-sized jammed block, squeezed past it and got to the base of the 90m corner, the defining feature of this route.

I headed up the first pitch, invigorated by the thought the day was almost over, just two pitches and we would both experience out first proper alpine bivvy on a route.

Matt took the second corner pitch and it pretty quickly turned into a full-on aid climbing battle. Matt is very competent but doesn't always seem to believe it – he seems to believe that most international climbers or those with flashy gear are guaranteed to be faster and more competent than he is, which is just blatantly untrue. There was an Argentinian team behind us, and now that our progress had slowed considerably they had nearly caught up to us and Matt seemed to be starting to crumble under the weight of his perceived incompetence. He offered to be lowered back to the belay and let me climb it, but there was no way I was having that – I had finished my leading for the day and had no desire to do any more. After telling him to get on with it, he finished up and did the final aid traverse below a roof on 60-year-old, rusty, flexing bolts, which deposited us at the bivvy ledge at 5 p.m.

We shared the bivvy with the Argentinian team of three who had been speeding behind us all day, slowly catching up. Luckily they were very friendly and all worries about some serious speed freak team trying to compete to get past us, as can so often happen in Chamonix, evaporated. It was nice to know that there was another friendly team about in case things went wrong the next day. We chatted and ate for a couple of hours, then I huddled into my sleeping bag between Matt and an Argentinian, glad for the respite before what was going to be a brutal day tomorrow.

We woke up as it started to get light, cooked a bit of porridge and packed our bags. No one wanted to start first the next morning, hoping the other team would go first and find the way on the hardest bit of the North Face of the Petit Dru. I accidentally ended up getting racked up before the Argentinians, so headed off first. I went off-route slightly a couple of pitches above and the Argentinians overtook us. The Allain crack was amazing and felt like a Fairhead prow E1/E2, and the rest of the North Face was what was to be expected of north faces in the summer – loose rock, some quality bits, lots of snow and ice and a huge ambiance! About 100m from the summit, we found the mythical hole in the mountain that brought us through to the south face about 100m from the top.

We were now fully just following our noses and hit several dead ends trying to quest our way up, each one adding a little bit of internal panic. Eventually, I just started to traverse around the mountain, with no real plan except to hope to find some easy way to the top. The ledge I was on ran out, I did a quick Russian rappel (hand over hand down the rope) to a lower ledge, turned a corner and saw two climbers! The initial relief was massive, I found out they were on the Drus traverse. I thought we were essentially done. It turns out they were pretty incompetent and there were five teams of them. They were seriously slow and were not being amenable to letting us past, getting their ropes stuck etc...

A comedy of errors occurred below the top of the Grand Dru when the third party got their rope stuck, the fourth started up, freed the rope then got their rope stuck in the same place, and then the same thing happened with the fifth! We finally got to the top of the Grand Dru and descended slightly over the snow-covered rocks to reach the abseil line. The descent from the Grand Dru is more serious than most, being about twelve hard-to-find abseils over a lot of loose rock with many stories of more competent teams getting off-route or benighted.

The Spanish teams were taking about 30 minutes at every belay station, holding up Matt, me and two very pissed off French climbers. I thought we could at least rely on the French team to snap soon and push their way past the Spanish teams, clearing a path for us as well, but unfortunately, we seemed to be stuck with the two least confrontational French men I had ever met.

It was around 5:30 p.m., starting to snow and looking like we'd all be stuck on the descent overnight. An hour and a half later at the third abseil station with nine more to go, I got too fed up, just clipped a carabiner into the belay as the last group was abbing off, stuck our ropes through and abseiled straight over the first two Spanish groups as they were slowly inching their way down their ropes, looking like they'd never seen a belay device before. Several more abseils straight over the next few groups and we were in the lead. For the life of me, I couldn't find the final anchor and ended up at two very poor pegs, one of which I was able to wiggle with my fingers. I placed a shite backup nut, equalised all three pieces and gingerly hung off it, keeping as much weight on my feet as possible.

Matt reached me, clipped in and I started abseiling very carefully to the glacier below. When Matt got down he handed me my nut back, having thought the pegs were OK… Arriving at the hut at 9 p.m., we started back down to Chamonix, managed to go the wrong way in the dark somehow, wasted several hours and ended up being so wrecked that when we sat down for a quick break we just couldn't get back up and bivvied for a third night on the path, leaving the ladders and the Mer de Glace to the next day.

Arriving back to Chamonix, we heard that the Central Pillar of Freney was still in good condition – or more like the approach and the Freney glacier was still passable and hadn't yet deteriorated into an unstable mess due to summer heat. After a rest day, and me vetoing Matt's suggestion of the Peuterey Integrale, we set about finding lifts to Val Veny over the border. Another valley-dwelling Irishman, Killian Buckley, had climbed it a week or so beforehand and was more than psyched to contribute to Irish ascents. Having only returned from the Drus on Tuesday, we were packing again Thursday night and left Cham at 4:30 a.m. on Friday.

Originally, our plan had been to walk up to the Eccles bivvy hut, stay there and go for the Pillar the next day. When we got there at 10 a.m., though, both huts were full! We just continued on to Col Eccles, thinking of finding somewhere nearer the route to bivvy. We had a bit of a moment there when the snow slid away from under Matt in a wet heap and he cartwheeled off one side of the snow arête – after having a quick think, I jumped off the other side. I'd always wondered if that would work and I'm glad to know it does. It's something else to add to the list of things that work in theory but I hoped I'd never test. A similar one to that was having to belay off a snow bollard once near the top of a mixed route out of a lack of anything else to use, then holding the seconder falling off vertical terrain with it!

Back to the Freney: Acting in conjunction, without really discussing the plan, knowing we really shouldn't do it but thinking it was just about justifiable due to the cold weather and fog blocking the sunlight, we just started downclimbing the couloir then traversing the upper Freney glacier to the base of the route. That journey could only be described as intense. The Freney is one of the more menacing glaciers that I've been on, technically being two glaciers with a massive cliff between the two sections. Ice from the upper glacier constantly breaks off and thunders down that cliff, obliterating anything in the way, creating tremendous thunderclaps as it does so that it feels like they're rolling up from just below your heels.

While there's really no danger from this, there is a huge amount of danger from above. We both nearly got done by rocks melting out of the semi-frozen walls and vertical icy goulottes towering above us, which created a proper shooting gallery-type scenario. Not helped by the fact the glacier was melting, the snow we were stepping on was trying hard to slide out from beneath us and the water running through the snow was soaking my gloves, causing some pretty painful hot aches. Anytime I paused to try to ease some of the pain, a rock seemed to fly right by one of our heads. Eventually, we made it to the base of the route in very thick fog, finally out of the firing line.

I was bollocksed by the start of the route; it may have been something to do with compressing what some people would call a two-day approach into a single fucking morning, but Matt just seems to have the endurance of a workhorse and he set off on several long simul-climbing blocks. I stuffed the tuna-avocado-chorizo baguette I had made myself for what was meant to be my bivvy dinner at the Eccles hut into my miserable face while waiting for the rope to go tight. When it did, I just blindly followed his lead, trying to recover. While the route was relatively safe, there was one table-sized block that dislodged itself along with a scream from Matt, smashing to bits literally right beside me and leaving me eating the grit suspended in the air.

Unfortunately, I decided to start pulling my weight again on a pitch that was pretty much just one long free solo up a 50m layback flake too wide to take any of the gear we brought. The next pitches were 'alpine shenanigan' pitches, climbing in rock shoes with ice axes in hand, swapping to boots and crampons part way up, swapping back into rock shoes, taking the axes back out and kicking steps with rock shoes etc. A beautiful small snow arête and a teetering rock arête brought us to the bivvy spot for the night, a 6x2 foot ledge, large enough to sit comfortably on but not lie down on.

So, happy to be done for the day, we settled in for the night and into some intimate spooning under the one sleeping bag. An atmospheric sunset along with a solitary small thundercloud in the distance, spitting out lightning, set the mood.

The pitches on the Chandelle the next day went by with a struggle, but without incident. Looking down from the top of the Chandelle to the several parties who had started from the Eccles that morning, all climbing over each other, we couldn't have been happier to get the entire route, one of Mont Blanc's finest, all to ourselves. Getting to the top of Mont Blanc was a slog, and a knackering descent of the Trois Monts route ensued, with us rushing to get back for the final lift to Chamonix from the Midi station. We only made it by 15 minutes.

The next week went by with zero desire to totter around falling down mountains, sleep on bum seats or be in any way wet, cold or hungry. Chilled out lift-to-lift ascents of routes were on the cards, and 'Super Dupont' on the Midi and 'Fidel Fiasco' on the Aiguille du Blatiere provided the chilled-out experiences we were looking for. Itching to make the most of the limited time, soon enough we were thinking about bigger objectives again.

Initially, we were going to head into the Grandes Jorasses to try the Walker Spur, a route I had specifically come to Chamonix for during the previous two summers. The first summer we never got the weather window, then the next summer a big rockfall caused it to be off-limits for any sane individual. This time, a big storm crossed though before the next weather window, causing the Grandes Jorasses to look like this:

We decided to give it a week to shed the excess snow and headed for a two-day climbing excursion to the Grand Capucin instead.

We jumped on 'Voyages Selon Gulliver' the first day, after hearing rave reviews about it being the 'best rock route in Chamonix.' And it was mega – up until pitch 10 when, due to a route finding error, Matt lowered off a bit of old tat that broke, sending him on a 10-metre winger. On the way down, one arse cheek hit off a ledge while the other didn't, causing some problematic 'separation.' Lowering him back to the belay, he had quite a bit of blood running down his leg and his hands were cut up. However, it was his arse he was worried about, specifically the fact that he thought he might have torn the bit you really do not want to tear.

We started to abseil off the route, with Matt looking more and more unhappy as we progressed. After a few abseils, he finally asked me to check his arse.

Now the last thing I really wanted to do at that point was look into the recess of his bloody arsehole, leading me to tell him to 'stick a hand down there and poke about or take a photo or something!' He duly obliged by sliding his hand down the back of his trousers, and it emerged blood red. Sensing that it was all really going to hurt the next day, we packed up and slogged back to the Midi. Arriving at 7:30 p.m. or so, we wandered in, relieved to be inside, when one of the lift attendants saw us and promptly kicked us out. I tried to explain in French about Matt's injury, nearly willing to pull down his trousers for a visual explanation, but the liftie was having none of it:

'Go to the Cosmiques!'

Not wanting to drop 50 Euros on a hut, we set up our sleeping bags in the ice tunnel just outside the door. An hour later, the liftie poked his head out again:

'No sleeping there. You must go to the Cosmiqes refuge. I'll be back in an hour to make sure you're gone.'

This time, I didn't argue at all. The main reason was that Matt had squatted down just outside of the ice tunnel to take a shite and his shins were visible. As the liftie started talking to me the smell of Matt's excrement hit my nose and I was willing to say anything to get the liftie out of there before he realised Matt was defecating at the front door of his precious Midi station.

We packed up our stuff and were getting ready to leave to sleep on the flat spot at the base of the ridge (there was no way we were ever going to sleep in the refuge), when the liftie poked his head out the door, having probably decided we passed the desperation exam and pointed us to a bench we could sleep on in the station.

Matt took the next day off to recover, but with my leaving in just over a week we wanted to make the most of the weather window that was approaching. However, it was getting smaller and smaller. Initially, our plan was to walk into the Walker Spur after two full days off, bivvy on the glacier then climb the route in a day and maybe bivvy on the other side on the way down. However, the three-day weather window was rapidly looking like we'd just have a day and a half of good weather, starting after only a single rest day. It was looking a bit ridiculous on paper. Matt couldn't really do any movements that caused him to raise his leg too high or too fast and we would be cutting it tight for time. But Matt was up for it and I spent so many years trying to climb this route, ever since my first trip to Chamonix, I just wanted to get it done. Therefore, early the second morning after arriving back to Chamonix, Matt taped himself together after deciding he was more psyched than broken, and we dragged ourselves to the first Montenvers train.

Stepping off the ladders onto the glacier, I was absentmindedly thinking through everything that would be necessary for the next few days and remembering if it had been packed or not, similar to repeatedly checking your passport in your bag when in an airport. Chucking the question 'You've got the JetBoil right?' at Matt, I wasn't expecting the 'You're joking, right?' response. Lovely. I had a litre and a half of water, Matt had a litre, we had a medium sized gas can for weight training but no JetBoil.

Feeling decidedly less up for this than any of the previous two Grandes Courses, we sped along the rocky, arduous approach to the base of the Walker Spur. Three or four hours after stepping off the train, and a bit of crevasse dodging, we were changing into rock shoes to start the route.

The start of the Walker Spur right up to the Rébuffat corner is pretty much just broken choss. It's not the most dangerous choss around, but it definitely made us go slower than we wanted. After a bit of faff, we made it to the Rébuffat corner, and after a bit more faff on the corner, we got past it. The experience so far was not the same as the other two big routes, there was a LOT of rockfall, and our plan to wait for warmer temperatures to strip of the snow had backfired somewhat – the route was pretty snowless so far, but it was still being stripped up above, causing us to have a few close calls with chunks of falling ice. I got hit on the arm by a very small bit and even that stung.

After this, a memorably wet traverse with an annoying snowy/icy section brought us to the base of the 75m dierdre. Dispatching this (wet), we arrived at a series of small ledges where, after climbing an extra pitch to search for anything else, we decided to settle down for the night. The sunset gave a Mordor-esque feel, my sitting bivvy wasn't great for sleep and Matt slept like a baby in the lying down spot. We had placed our water bottles under some intermittent drips of water in the hope they may fill by the morning. Dinner consisted of pouring cold water into a freeze dried chicken curry meal and crunching our way through the frigid mixture. Between having no way of melting snow or cooking, the heavy-ass sacks and general burnout after an intense three weeks, motivation was dropping.

Thunderstorms were forecast for the evening on the second day, so we got shifting as soon as it was light. Two cereal bars, a quick pack then leading off through some very wet rock, some more Russian rappelling, some steep rock and we made it to the crest of the spur.

We could finally feel like we were moving, and I started to enjoy myself – until the red chimney. This was basically devoid of the ice that holds the rock together. It was dripping with water and gave the most nerve-wracking four pitches of the entire trip with shitty rock and poor belays of manky pegs behind broken rock, with the overhanging chimney above spitting out rocks whenever it noticed we were still there. The route never gave in and even the final pitch was a pain, but we finally made it over the cornice at the top.

The descent was disgusting. Down scrambling loose ridges and crossing steep glaciers, never too hard, never easy enough to not have to concentrate on every footstep. There were many short abseils involved, and on one of them I was abseiling to a sloping ledge about 30 meters above a glacier we were trying to reach, looking at a large amount of rope coiled on the ledge below me when:

WHOOMPH

I was flying through the air and was suddenly stumbling backwards across the ledge, one strand of rope nowhere to be seen. Steadying myself just before the edge, I saw it two metres above me, the other was still in my belay device – only one end had been coiled on the ledge and I'd abbed straight off the other.

Seriously embarrassed, I didn't tell Matt. Instead, I just told him to watch the end of the short rope as he was abbing towards me, then expelled the incident from my brain.

An age later, mentally ruined, physically exhausted, just done with Alpinism, we reached the Boccalatte hut. Five minutes later, the heavens opened, unleashing a biblical thunderstorm that lasted all night; a final fuck-you from the mountain. The hut warden was hammered and offered us a spot for the night. The next morning we realised he didn't mean for free, and neither was the food he gave us.

We finished the trip climbing 'Etat de Choc' just over the Swiss border, an amazing route in an idyllic, peaceful setting where you just want to stay forever. However, literally nothing went wrong, which isn't in keeping with the rest of the trip, so I won't bother you with it.

Being stuck indoors for so long gave both of us a serious drive to do as much as we could before everything got locked down again. For me it drove home the fact that the mountains won't always be there next year as, alongside the virus, routes are collapsing all over the Alps, you could fall out of love with the activity, injuries happen etc. Basically, as I wrote earlier on in this piece, I was way happier than I was previously to push my little boat out, whether through starting routes exhausted, sleep deprived, not recovered, trying some things that weren't in tip-top condition, I just didn't care.

Getting a glimpse of a future without access to mountains gave me the desire to want to experience it all, now. Writing all this in the middle of the third lockdown (end of March 2021), I could seriously do with a trip like that again and was glad I was able to leave as a mentally and physically exhausted shell of a human. I thought I'd end it on that note following comments a friend made after sending them a draft of this piece: 'Man, you're going to get slated by some American climbers who'll say you two are way too blasé, and that you shouldn't be going anywhere near alpine stuff. it doesn't come across like you fully understand the risks.

As a little postscript, I'd like to thank David and Scott Williams for giving me their food, clothes, beer and lots of borrowed equipment over the years — who needs sponsors when you've got friends like those!

Comments

Brilliant write up, thanks :)

Really enjoyed that, good read!

Was Matt's gem actually precious?

Really fun article thanks. Captures all the joy and psyke of climbing!

Great read, excellent. Gawd! I'm missing having not done anything big in the past year!